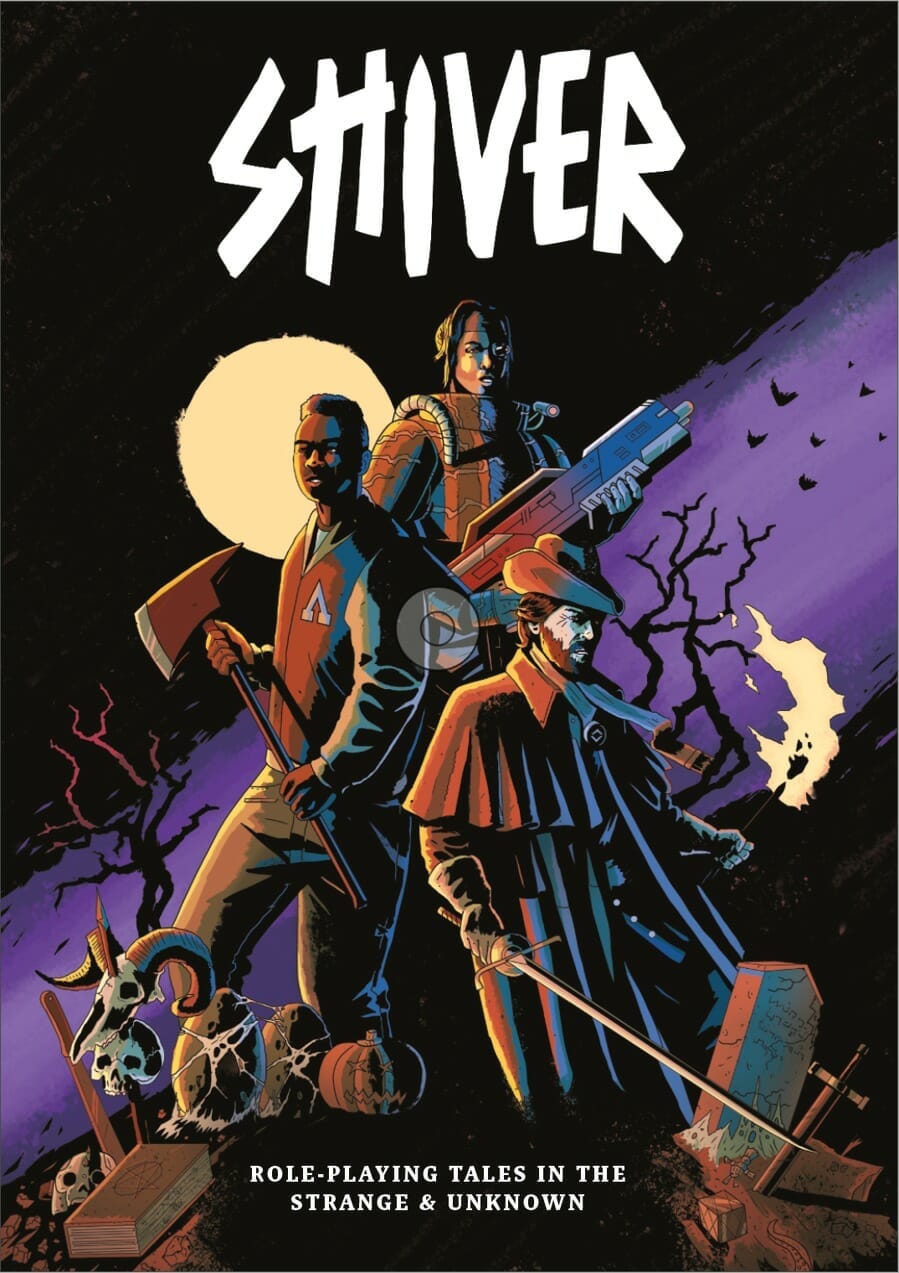

Lately I have been thinking about social interactions and personal relationships in roleplaying games, which lead to an interesting discussion with some of my players. They’d been talking to someone about the game Shiver. One person had advocated for the game, stating that it was “Like Call Of Cthulhu but with better roleplaying”.

This diagnosis confused the hell out of me. I love both of these games, but neither one of them has a greater focus on the roleplay elements of a game. In fact, if we look at them on a purely mechanical level, then Cthulhu has a deeper mechanical interaction with the idea of social skills – the core game has persuasion, intimidation, fast-talk, charm, and psychology with fine details about which skill can accomplish what. It has gradations of different social skills in different setting too, like the fact that the Regency Era setting comes with a ‘reassure’ skill that allows you to sooth the nerves of your companions with a supportive word. Whereas Shiver, a more free-form game, has basically one human interaction trait (Heart) and no extra specific social rules unless you pick specific abilities from the socialite archetype.

So what lead to the advocate making this analysis? Well, it’s probably a bad equation. Either they’d equated the dynamics of that group being more roleplay focused as something inherent to the game or they’d confused the clever things Shiver does with its narrative agency with additional roleplaying content. Because those two things aren’t the same. Realising it was even possible to make these two misalignments in thinking made me go on a series of rabbit holes considering how we define roleplaying and then if we even need social mechanics. Maybe we was time to ask ‘What even is roleplaying anyway?’

Don’t They answer That In Like Every Roleplaying Book Ever?

Yes, in the majority of RPG core books we have that obligatory paragraph or so where we explain what a roleplaying game is in the broadest terms. And it’s useful for new players, but most of us skip it, right? And we go on knowing what roleplaying is because we’ve done it lots. Except I wonder if most of ever really look at the act of roleplaying in a roleplaying game and what it actually is, where a game gives us ideas and things to do. So let’s go beyond baby’s first steps and look at some definitions through examples.

Shiver is a great game. It’s very free-form, with players rolling special dice and trying to get enough of a certain symbol in order to complete an action.

The example in the book is a social one, with players trying to roll enough ‘Heart’ symbols in order to get into a club. When a player succeeds, the fact some of the other dice came up ‘Grit’ symbols means the group can decide that maybe the door guard was largely intimidated by the social attempt and is a bit wary of the group after he lets them inside. This is an additional feature that is not necessary to play, but it is still included.

Outside of combat, the system is only very loosely codified and open to interpretation amongst the group leads to a more shapeable narrative by the players. There’s also a mechanic that certain types of failures trigger narrative events in the game, which means players can see that their rolls are having an effect on the story, that mechanically each interaction with the plot they choose could spell long term disaster.

This narrative design is a sort of genius, with players experiencing tension which translates to their characters. But it’s not Roleplaying mechanic. It’s doesn’t actually give us any additional reason to choose to roleplay, especially with each other, where often no dice are involved. It actually sometimes might prevent us from taking an action that requires dice because that might result in a roll that triggers a bad narrative event. Instead it’s a Narrative mechanic, based around creating a Mood. That is the mood of a horror stories sense of impending doom and ‘ticking clock’ feel.

All this is to say, the term ‘roleplaying game’ is such basic phrase to define what we are doing in RPG games. We are playing a role, sure. We’re also semi-acting, making tactical gaming decisions, building a narrative together and probably eating snacks. Okay so that last one is irrelevant, but when we think about what is happening in a game and understanding what about a game works for us, it’s important to understand what each game does well or is even engaged with. Because, if after that conversation, my player had picked up Shiver expecting a game that delivered some detailed complex social game with loads of roleplay heavy mechanics, they’d have been disappointed. Especially as that player stated they often use the social mechanics of a game they are playing to substitute for the their lack of actual, real life social skills. So the lack of definition on what the ‘roleplaying’ part of a game is might have been damaging here. While I’m absolutely sure the Shiver advocate is having a great time in their game, translating what is great about that experience has gotten lost.

So for a second, let’s inspect another part that might be true. Maybe the advocate in the Shiver game is feeling like the free-form lack of social game rules have given them a chance to spread their acting wings and really interact with people.

The space between the rules is where the interactions with people happen. And this can be brilliant. It’s possible to overdo social mechanics, at which point they become narrative elements again. If you’ve ever played a PBTA game and found yourself wondering ‘Am I doing this because my character would, or because a mechanic sort of makes me do it to deliver a certain story?’ then you know what I mean. As much as my players were playing moody teen superheroes, they sure did act out in self-destructive ways a lot and then have to swallow their pride and have interactions about this over and over to remove conditions. It’s what the genre demands but it also removes a little bit of choice from the players. So maybe a little lack of definition between those rules really gave the advocate a chance to inhabit the character.

The question arises though: how is a lack of defined rules for social interaction any different to a game like D&D? Well, it isn’t to some extent. One of my big bugbears is when players say something like ‘We had a great session, we didn’t role any dice at all!’. I get what they trying to say. But if your best sessions are when you aren’t actually using the game rules, why the hell are you playing that game? It’s clearly not interested in doing things with the parts you love. Any game could be used and maybe some of them would reward your character for that playstyle.

So do we need specifically ‘interpersonal roleplaying’ rules in our game? How much is too much? Where do we draw the line? In order to inspect exactly what we can do, the choices we can make and how roleplaying specific rules serve an audience, I’m gonna need more space. So I’ll see you all back here for the next column. Consider that me borrowing some narrative building from Shiver.