Today is the start of Teach your Kids to Game week at DriveThru RPG. There’s a sale of family RPG material all week and you can keep up with the events via their Facebook and Twitter profiles. Worth keeping an eye on if you’ve little minions of your own.

Eden Jones-Hinds, formerly of Oak Mountain Intermediate School in Birmingham, Alabama, is now principal of Briargrove Elementary School in Houston, Texas. She heard about Monsters and Other Childish Things from a friend and decided to use it as part of a creative writing curriculum for fifth-grade students. She had never played a tabletop roleplaying game before.

Newcomers can read a two-page summary of the Monsters and Other Childish Things rules here. (PDF)

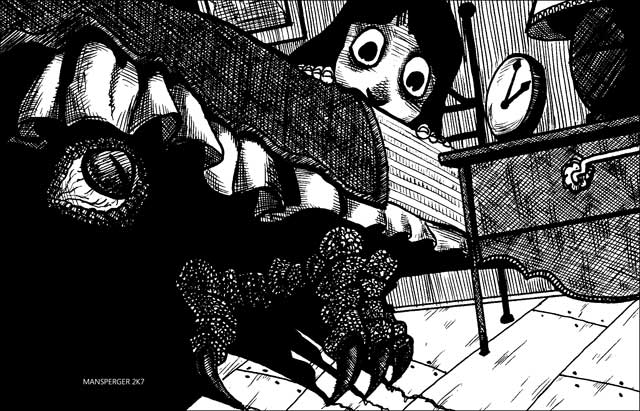

Monsters and Other Childish Things is © and ™ Benjamin Baugh. Illustrations are by Rob Mansperger, © 2007.

Benjamin Baugh’s roleplaying game Monsters and Other Childish Things (Arc Dream Publishing, 2007) opens the virtual door to a world of creativity and power. Played in a school setting, it catapults problem-solving, making connections, and synthesizing relationships to a new platform for students. Students are challenged to make decisions that involve the scientific method, manipulating variables and using negotiation to survive. Probability controls the game and shows students how daily outcomes can be visible through statistics.

Monsters was introduced to a group of eight fifth-graders from Oak Mountain Intermediate School in Birmingham, Alabama, in a series of 45-minute sessions. The teacher served as facilitator and Game Moderator (GM).

Teacher Preparation

In preparation for the game, the teacher should read through “Appendix A: How to Play Roleplaying Games (.zip)” and “Appendix B: How to Run Roleplaying Games (.zip)” by Greg Stolze to develop a strong sense of how the game works. The game is a fictional story where things aren’t always as they seem. The teacher can create a wide network of twists and turns for the players to explore.

One of the most exciting preparation activities is character development. In order to do this and help the students do it, the teacher must develop a strong verbal visual of the story setting. In Monsters, it is a school quite like what the kids are familiar with but which offers quirky class scenarios, supernatural adventures, and conflicts that raise the stress level.

Since fifth graders need a “G-rated” world, the teacher should think through a storyline ahead of time—or rather, how the story begins and how it might evolve and change according to the players’ decisions. The GM cannot control the game to determine the outcomes but should have several ideas of how the story can change. The setting always stays the same, the situation can’t. Be prepared for the unexpected.

The climax of the story is really determined by the actions of the players, but it is good to have the elements of a great one in mind. At Oak Mountain, the teacher-GM planned to lead students to a school situation where bad teachers along with their monsters held students in the lunchroom, forcing them to eat sludge infiltrated with brain-controlling bacteria. As play emerged, two student monsters were captured and turned into the form of spaghetti and meatballs on the serving line, ready to be eaten by their own owners. One student had already eaten the bacteria and was now under the mind control of O’Malley the Anti-Drug dog, who was really a rubber suit that disguised the mad science teacher. Who could save them now? That was up to the student characters and their monsters!

Monsters and Metaphors

In most Monsters and Other Childish Things games there are only four or five players. Due to the larger number of students in class, the teacher asked them to choose partners, one to be the kid character and the other to be that kid’s monster. Students were divided into two groups for directions to be explained more clearly.

Three boys and five girls surrounded a table to discuss the idea of what a monster is and looks like. Monsters come in all forms. With the help of a graphic organizer, the teacher led the students into a lesson of descriptive writing. Monsters can be what we see in our dreams or what we fear. A monster can be the size of something we don’t like to do or even a colossal ice cream sundae that’s enjoyable but seems incapable of being eaten. We all have monsters, don’t we?

Students explored adjectives, similes, and metaphors, dabbling with analogies and irony in discovering new ideas and concepts. “Monsters are sticky and can cause stains,” said one student. “If it is a problem, you may be nervous about what to do. And if you handle it wrong, what you did will stay with you, and you can’t forget about it.” Wow! What a thought.

Students were asked to write expository essays about their “monsters,” exploring their own personal strengths and weaknesses in dealing with certain situations. The first paragraph contained the introduction of their topic and three problems caused by a “monster.” The following paragraphs explored the three problems and how they chose to deal with it. The last paragraph summarized the topic and how it was solved for a strong conclusion. Students shared their paragraphs as they wrote, taking critiques, and rewriting making it fluid. Six Traits of Writing were expected: Organization, Fluency, Word Choice, Voice, Ideas, and Conventions.

Kids as Characters

Characters give the game life. Each student has one kid character whose role the student plays in the game, and each student’s character has one monster who is friend and ally to that character and to that character only.

It’s up to the students to describe and define their characters. Their characters can be very different from the players themselves. The students began by looking at physical appearance. Given the leeway to be as fictional as they chose, students looked for ideas of people they expected to see in the school environment.

Another essay evolved around the Monsters and Other Childish Things character sheet (PDF), called the Permanent Record. The teacher asked students to interpret this “performance evaluation rubric” before explaining it. This forced students to read informational text on their own. After discussion, the teacher spent time explaining how dice are connected with this rubric. This is where pages 22-24 of the paperback rulebook came in (pages 15-16 of the hardback), the section on “Stats and Skills.” (Students asked for more skill points than the usual 15, so the teacher raised the number to 25 with the instruction that if a student failed a roll, the GM could decide to deduct a skill point from the area of her own choosing, adding more stress to the game.)

For the essay, the students were asked to develop a first paragraph that included the Essential Data section of the character sheet, a second paragraph or more to include the Subjective Evaluation section, and following paragraphs to include Relationships. Players need to understand all these components to be able to manipulate them in a game. These essays were shared with the group in order for everyone to see the characters’ relationships to the environment and each other.

Their Very Own Monsters

As this group developed their characters, the other set of students created the monsters (PDF) of the game. They also developed essays to describe each monster’s appearance, personality, favorite things, ways to hide, and relationships. The students were asked to make a strong visual of the monster.

Partners worked together to tweak each other’s work and determine each kid character’s stats and skills, as well as their monster’s hit location numbers, dice, and qualities, based on the artwork that they created.

When these essays were completed, the characters and monsters swapped essays with their partners. The partners drew the characters based on what they interpreted in the essays.

The teacher facilitated conversation of how the character and monster would work together, expecting students to form relationships and communication with their partners. Artwork was then shared with all game players as they introduced themselves to the school setting for the game.

After characters and monsters were developed fully, the teacher encouraged each student to create a stuffed animal or other item that would represent the partners as a character and a monster. Some students wore matching hats or matching T-shirts with hand-drawn character and monster.

Learning the Rules

The teacher went over the basic rules of the game: the ways students would describe their characters’ and monsters’ actions as they tried to solve conflicts, the function of kid character stats, skills and relationships, and the function of monster powers.

The teacher talked about the rules for determining the “speed and finesse” of actions, and the game mechanics for a roll’s “Width” and “Height” on page 25-28 of the paperback (pages 16-18 of the hardback).

The teacher explained about the One Roll Conflict Generator on page 98 of the paperback (page 64 of the hardback). This was pretty easy to explain to fifth graders.

Playing the Game

After four work sessions, it was time for the best part — playing the game!

In Monsters and Other Childish Things, the more dice you can roll, the better your character will do. And characters have relationship scores that give them extra dice to roll. As you develop the rising action of the story, it is imperative for the teacher to stress urgency and to direct students to evaluate the depth of relationships that can help them achieve a desired solution or goal. The storyline should encourage finding creative solutions and getting help from others. Kids love dice. Anytime they can increase the number of dice, they will want to do so. This takes guidance on the first couple of runs. The GM should be willing to ask leading questions: “How do you see this being resolved?” “Who can help you with this task?” “What skills and talents do you have to get the job done?”

To resolve conflicts, the students wrote expository essays and the teacher asked them to find ways of resolution. From this, a list was generated to which students referred for ideas. The teacher-GM used the same list to decide the actions of GM-run characters, and to provide traps, challenges, and new conflicts for the students’ characters to overcome and resolve. Students were especially fond of their make-believe characters dodging, using disguises, and punching.

The characters and monsters included in Monsters and Other Childish Things have great suggestions for ways they can interact with the player characters. The GM should introduce them to help develop the storyline. The GM should create verbal visuals as a model to encourage students to describe their characters’ and monsters’ actions more strongly. Inserting character voices and actions encourages students to create and practice voices and actions of their own, making the game even more fun for everybody.

“I didn’t know I wasn’t supposed to eat him.”“Well, you did! Now what are we going to do?”

“Well . . . skip dinner, for one thing. I couldn’t eat another bite.”

“This isn’t funny.”

“It’s a little bit funny.”

“When they find out Dad’s boss got eaten, Dad is going to get fired, and then we’re going to have to move into a cardboard box behind the Sip’n’Dash, and I’ll have to share my corner of the box with Janie because we won’t be able to afford a box big enough for me to have my own space anymore!”

“You said that all in one breath.”

“I can swim all the way across the pool in one breath.”

“That’s pretty awesome. We should go swimming.”

“OK, but—hey! You distracted me!”

“I just want you to be happy. You worry about swimming all the way across the pool and BACK again in one breath, and let me worry about your Dad’s boss.”

“How? How are you going to fix this?”

“OK, give me a second . . . SMUUUUUUUUURGUAH! There.”

“That . . . how . . . Mr. Wilkins?”

“Sure! Ever since I kicked the crap out of Chameleon Pete last week, I can turn into anything I want.”

“No kidding! So like . . . you could turn into Miss July?”

“Easy peasy, my friend. Just let me eat her up, and I’m your dream girl.”

“Ah. . . . We’ll put that one on the ‘Maybe Later’ shelf, right?”

“Right.”

“Let’s get back downstairs before Mom starts worrying her meatloaf is cold.”

“I shudder to think of your mother’s meatloaf.”

“You just ate a full-grown CPA! With ballpoint pens and shoes and wallet.”

“He tasted like salty hot dogs.”

“I’m gonna barf.”

From Monsters and Other Childish Things

By Benjamin Baugh, © 2007