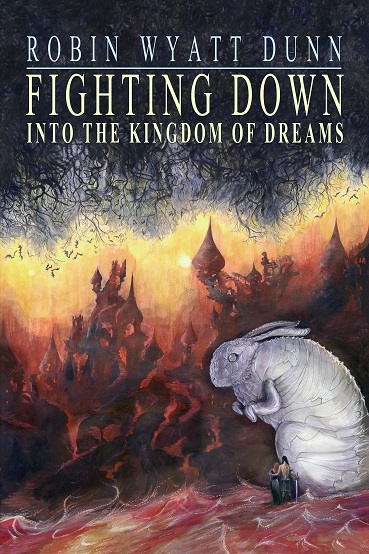

Robin Wyatt Dunn is the author of the forthcoming fantasy Fighting Down into the Kingdom of Dreams. In the book we encounter a giant metal rabbit, the lost dreaming of the Rat City of Roth and re-fight old battles with fusion weapons in a parallel New York City.

Geek Native invited Robin to write a “From the Inkwell” article on the nature of worldbuilding. It seemed appropriate. He was kind enough to agree.

If Fighting Down into the Kingdom of Dreams isn’t yet available to read when you discover this post you will still be able to mark it “Want to Read” at Goodreads.

Worldbuilding is a funny business, in more ways than one. Both funny ‘ha ha’ and funny ‘weird,’ and a ‘business’ in the sense that it keeps me busy, not in the sense that it makes me money. It generally loses me money!

But worldbuilding isn’t about money, it’s about fucking with your head. In this respect, I regard novel-writing as no different from legislation in Washington: like it or not, it’s going to come to your town, and it’s going to change your behavior, in ways you will not be able to predict.

A fair number of writers agree completely with Homer, that inspiration, the Muse, does come from somewhere else. Burroughs, for instance, regarded the whole of language as an evil self-replicating transmission from outer space. (But Burroughs also believed that women were a different species, so we’ll have to take his wisdom with a grain of salt). Still, it’s been my experience that the best writing does feel like it’s coming from elsewhere; I’m just the conduit.

This means that my variety of world building is more like tuning in to a distant radio station to make it audible, or pruning a horrendous trans-dimensional growth from the nearest wormhole like a gardener might prune an overeager hedgerow. I listen to “the voices” and do my best to pick the parts that make sense, and toss the parts that make too little sense.

Some will (and do!) claim (perhaps including me!) that my style is too literary, that my concerns are too academic, and that my approach is too experimental. Well, fine. It’s what I’ve got, you don’t have to like it!

What I like about my style, a mix of stream-of-consciousness, absurdism, and traditional linear narrative, is that it’s got forward motion but it retains a herky-jerky framework too; so that while I never leave the reader completely at sea, I don’t exactly point out all the landmarks along the way either. You have to do some of the sailing yourself.

Gene Wolfe is one of my biggest influences, but I’m more experimental than Wolfe. What I borrow (steal!) from him is the elliptical, borderline-recursive nature of his narrative arcs, that constantly swarm back on themselves, resisting easy explanations.

It’s been my experience that science fiction/ fantasy readers, much to my surprise, are mightily conservative, both in their politics and in their literary tastes. I find this unfortunate. Modernism is arguably a 150-year old literary phenomenon, yet it’s only now starting to become acceptable in genre fiction. (Note that Wolfe only got his Grand Master crown last year, in his 80s, while more traditional prose stylists often get their “crowns” much younger).

As to the world itself:

I think the book’s themes are ultimately more important than the mechanics of “which parts fit where.” Truth be told, this is in part because I make little effort in this book to explain the mechanics of how the various dimensions fit together, how physics and other scientific laws have been stretched, or disregarded, to make the world function. In my experience as a reader, I usually prefer this approach to the one where explanations occupy a substantial portion of the text. Remember that science itself is to a degree an imagined phenomenon, and that consciousness and matter are not separate entities. (This is a concept that I use repeatedly in this book, which can be traced to the linguistic overlap between the English words “whit” and “wight” – thing, and being. That is, for our ancestors, things and beings were the same thing).

So, the themes are these: love, loss, memory, desire (for newness, adventure, home), pain, family. Like any good (or halfway good!) writer, I make these human concerns the central focus of my book, rather than the logistical frameworks upon which the narrative hangs.

These human themes are complicated to a degree by the fact that the narrator of the book is not a human being, but a huge, interdimensional, godlike metal rabbit named The Hrudu Man. But perhaps it’s fair to say that my efforts to make this nonhuman creature display human emotions and concerns parallel the ongoing scientific/ humanitarian effort to remind the human race that our fellow mammals share nearly all our emotions and conceptual frameworks, that our brains may be bigger, but most of what connects us is inarguably intimate, and an area of ongoing scientific/ literary investigation. Incidentally, this may also kill “the pathetic fallacy” – because it’s not a fallacy if the natural world and the plants and animals in it actually do feel as you do, in a verifiable, scientific manner.

I hope you enjoy the book!

Sincerely yours,

Robin Wyatt Dunn