This week we’re celebrating International GM’s Day with a big sale at DriveThru RPG. It’s the largest sale the retailer runs all year.

So many great choices, lots of temptations… might make it hard to make a decision. If you’re looking for a new RPG to try how do you find one among all the games available.

You might use DriveThru RPG’s star system to see which games fellow roleplayers rate highly. If you do that then one of the games on your shortlist would be the superhero RPG from Arc Dream Publishing called Wild Talents. Written by Dennis Detwiller, Kenneith Hite, Shane Ivey and Greg Stolze, illustrated by Todd Shearer, the game reviews well.

The following is are three extracts from the RPG; the introduction, a section from the One-Roll Engine and from the combat chapter.

Wild Talents

Welcome to Wild Talents Second Edition.

Wild Talents is a roleplaying game that emulates the worlds of comic book superheroes. You make up the characters and their adventures. From the deadliness of Top 10 and V for Vendetta to the four-color action of Spider-Man, JLA, and The Avengers, Wild Talents is built to handle it all.

Wild Talents aims to capture the dynamic action of superhero comics. Superhero games should be fast and exciting. The rules should propel the action, not slow it down. They should be flexible enough to handle anything, quickly, without a lot of page-flipping.

Wild Talents does this with a simple, intuitive rules set called the “One-Roll Engine,” or O.R.E. All character actions are resolved with one roll of the dice. In combat you don’t roll to see who goes first, then again to see if you hit, then again to see if your power works, then again to see how much damage you do, then again to see how far you knock your target across the street, and so on. And you don’t need to spend a lot of time looking up rules and results for every single action.

In Wild Talents, you roll once. That tells you all you need to know.

Creating a character in Wild Talents is simple and straightforward, and the modular construction of the rules allows you to tweak them to fit the tone of your game, from the deadly to the over-the-top, instantly.

In its standard, unmodified rules, Wild Talents strives for a “realistic” feel, to give a sense of consequences for using superhuman powers with abandon — or failing to use them properly when the time is right. But every chapter is loaded with options to “open up” the game to four-color action and beyond.

The result? A different kind of superhero game. A game that plays fast and lets you easily adjust the rules to your style, making anything possible—from lighthearted brawls to take-no-prisoners realism.

Wild Talents is your game.

Chapter 1: The One-Roll Engine

The Wild Talents rules encourage speed and realism without sacrificing consistency or requiring endless rolls. We call the rules the “One-Roll Engine,” or “O.R.E.” Originally developed for Godlike, the O.R.E. keeps game play fast and exciting by extracting all the information you need—speed, level of achievement, hit location, damage; everything you need to know—from a single roll of the dice. Wild Talents is also highly modular, allowing the rules and “feel” to be easily altered to suit any style of game play.

What Makes a Wild Talents Character?

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of Wild Talents, let’s explain the basics—the essential components of every character and the kinds of things they do in the game. This is a basic introduction to the game; we go into greater detail later.

Character Points

Each Wild Talents character gets a number of character points (Points) with which to “buy” abilities. The more Points you have, the more things your character can do.

Stats and Skills

Statistics (or Stats for short) describe the basic qualities of every character. They tell you how strong and smart your character is, how coordinated and commanding, how level-headed and how aware.

The Stats are Body, Coordination, Sense, Mind, Charm and Command. They’re measured in dice. In normal humans they range from 1 die to 5 dice (or 1d to 5d in game shorthand). In superhumans, who can have Hyperstats and Hyperskills, they can go up to 10 dice (10d).

You don’t roll those dice to determine your Stat; instead, that’s the number of dice you roll when you want to use the Stat. So if you have two dice in Mind, whenever you try to out-think someone you roll two dice. However, usually whenever you use a Stat to do something, you’re also using a Skill.

Skills are specific learned abilities such as driving a car or speaking Vietnamese. Like Stats, Skills are measured in dice, from 1 to 5 dice in normal humans, up to 10 dice in superhumans.

Every Skill is based on a Stat—driving a car fast around a corner requires balance and hand-eye coordination, so the Driving Skill is based on the Coordination Stat. To use a Stat and a Skill, roll the dice you get for your Stat and the dice you get for your Skill. If you have 2d in Coordination and 3d in Driving, you roll 5d.

Base Will and Willpower

Most characters, normal and superhuman alike, have a Base Will score that defines their internal resilience, confidence, and drive. It rarely changes.

Most superhumans also have a Willpower score, which drives their incredible powers. Self-confidence is crucial to achievement; tragedy and defeat sap the abilities of the most powerful hero.

Base Will and Willpower aren’t measured in dice like Stats and Skills; they’re measured in points that you spend to do superhuman things. Base Will starts equal to the sum of your Charm and Command Stats, but you can improve it by spending character Points. Willpower starts equal to your Base Will. You can also improve it during play by accomplishing great things.

Motivations and Experience

Each character has two essential motivations: one Passion and one Loyalty. A Passion is some personal, internal desire or belief that the character pursues. A Loyalty is an external motivation, some other character, group or cause that the character serves or defends. Each motivation gets a numerical rating; divide your Base Will score between them. The greater the motivation’s score, the more Willpower points you can get in the game by pursuing or defending it—and the more you can lose if you fail to do so.

Your character gets better at doing things by spending Experience Points (XP), which you earn at the end of each game session. Having disadvantages — or, more accurately, playing your character’s disadvantages faithfully—allows you to earn more XP.

Powers

A power is some ability that is impossible to ordinary human beings. Flight is a power. Being able to lift a bus with your own hands is a power. Shooting laser beams from your eyes is a power. Being able to teleport across the street is a power.

As you might guess, only superhumans have powers. Of course, some powers are built into objects that anyone can use, even normal humans—but it takes a superhuman to create that kind of object.

In Wild Talents, superhumans are sometimes called Talents and their powers are called Talent powers—although occasionally the powers themselves are called Talents, too. We’ll try not to confuse you.

We also call powers “Miracles.” That doesn’t imply that they have some divine origin (although in your game they might; it’s up to you), but to drive home their sheer impossibility. These aren’t works of extraordinary skill or adrenaline-fueled feats. They’re beyond anything human.

However, some powers enhance or exaggerate human abilities. A power might simply add dice to your Body Stat to make you superhumanly strong, or it might add dice to your Computer Programming Skill to make you impossibly proficient with computers. Those powers are called Hyperstats and Hyperskills, because they increase Stats and Skills.

If your power doesn’t add dice to a Stat or a Skill, it’s measured with its own dice, from 1d to 10d. In that case you don’t roll them in conjunction with a Stat’s dice. You roll the Miracle’s dice pool alone.

Chapter 4: Combat

Here’s where we get into some of the most important rules in the game—the things that can injure or kill your character. Because combat and other threats change the game so drastically, the rules for them are quite specific.

Sure, it may be important for you to reroute the heliship’s power with your Control [Electricity] Miracle, but usually you don’t need to know the details—just whether it worked or not. But if some goon is trying to plug you with a sniper rifle, you need to know exactly when and where he does it.

The Three Phases of a Combat Round

Each round of combat is broken into three phases: declare, roll, and resolve. When all three are done and every character in combat has acted, the next round begins and the cycle starts all over again.

1) Declare

Describe your character’s action. The character with the lowest Sense Stat declares first, because a character with a higher Sense is more aware of what’s going on in the fight and is better able to respond. Non-player characters declare in order of Sense just like players. If two characters have the same Sense Stat, use the Perception Skill and the Mind Stat (in that order) as tiebreakers.

When you declare, make it short and specific. That doesn’t mean you can’t make it dramatic. “I smash the guy in the face” is the same action as “I’m glad you emptied your gun at me, ’cause now it’ll be warm when you eat it!” but one is a little more engaging than the other. If you’re doing something special—dodging, attempting two things at once, aiming at a specific body part, helping a teammate with some action, or using a martial arts maneuver – say so now.

2) Roll

Each character rolls the dice pool appropriate to the declared action—usually a Miracle, a Stat, or a Stat + Skill dice pool. Since all characters have already declared their actions, all roll at the same time and figure out their actions’ width and height.

3) Resolve

The character with the widest roll always acts first. If two sets are equally wide, the taller roll goes first. All actions are resolved in order of width. If five characters roll 5×5, 3×6, 4×6, 2×3 and a 3×10, their actions are resolved in the following order: 5×5 first, then 4×6, then 3×10, then 3×6, and then 2×3. This means any action wider than your roll happens before your action—even if you’re trying to dodge or defend against that attack. If it’s wider, it happens before you can act or react.

When an attack hits, it immediately inflicts damage. If you suffer any damage before your roll is resolved, you lose a die out of your tallest match—since being punched, stabbed, or shot is very, very distracting. If your set is ruined (reduced to no matching dice), the action fails, even if you rolled a success. You lose a die every time you take damage.

That’s all there is to a combat round. Everyone says what they’re doing, they roll, actions happen in width order, and then it starts over again.

Damage

Damage in Wild Talents is specific. When you’re hit, a single roll of the dice tells you exactly where you’re hit and for how much damage.

Types of Damage

There is a world of difference between getting punched in the gut and getting stabbed there. A punch aches and bruises, but unless you’re pummeled for a long while you’re unlikely to suffer any lasting harm. Being stabbed or shot is entirely different — your internal organs are re-arranged and exposed to all kinds of germs, viruses, and pollut-ants. Damage that penetrates the skin is serious.

In Wild Talents there are two types of damage: Shock and Killing.

Shock damage shakes you up and can be dangerous in the short term, but is usually shaken off quickly. It represents blunt trauma, concussion, shallow surface cuts, or light bleeding.

Killing damage is just what it sounds like—damage that can quickly end your life. It represents puncture wounds, deep cuts, organ trauma, ballistic damage, heavy bleeding, or burning. Sometimes Killing damage is reduced to Shock damage due to armor or other effects; when this is important, 1 point of Killing damage is equivalent to 2 points of Shock.

Hit Location

The location of an injury is usually much more important than the amount of damage; given the choice between having someone stomp on my foot or my face, I’ll pick the foot every time.

If you take a wound for both Shock and Killing damage, always apply the Killing damage first, then the Shock.

Once all the wound boxes in the head are filled with Shock damage or a mix of Shock and Killing, you’re unconscious. If your head boxes fill with Killing, you’re dead.

When your torso fills with Shock or a mix of Shock and Killing, your Body and Coordination are reduced by 4d each until you recover at least 1 point of Shock. If your torso is filled with Killing, you’re dead. At the GM’s option, if you take a serious wound to the torso—three or more Killing damage from a single wound—you may take one Shock per round from bleeding until you get medical treatment.

When a limb is filled with Shock damage or a mix of Shock and Killing, you can’t use it to perform any Skill or action. If it’s a leg, your running speed is cut in half; if it happens to both legs, your movement is reduced to 0.

If a limb is filled with Killing, it’s seriously damaged and may never be as good again. The GM decides the exact effect based on the nature of the attack and injury and the quality of medical care you receive. Maybe it reduces Stat + Skill rolls using that limb by –1d because it never quite heals properly, or you lose a wound box from that location permanently; or the attack might cut it clean off.

Once all wound boxes in a limb fill with Killing, any further damage to that limb goes straight to the torso.

At the GM’s discretion, any serious injury may call for a Trauma Check (page 63).

EXAMPLE: A fanatic from the End Gang kicks The Red Scare with a 3×5. That does width in Shock damage, so The Red Scare takes 3 Shock to hit location 5, his right arm. The next round, another End Gang thug stabs The Red Scare with a big knife that inflicts width in Killing, rolling 3×6. The Red Scare suffers 3 Killing damage, again to the right arm. He started with 5 wound boxes on his right arm, so 2 of the 3 Killing points fill the 2 empty wound boxes. The third point of Killing damage is divided between two of the three boxes that already have Shock. The Red Scare’s mauled right arm now has 4 Killing and 1 Shock inflicted on it—it’s so badly hurt it can’t be used. One more point and it might be unusable forever!

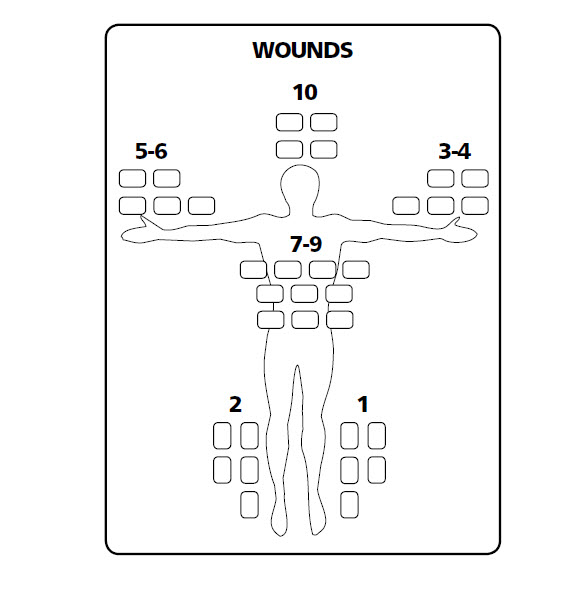

The Damage Silhouette

Every character sheet has a damage silhouette with a bunch of wound boxes representing how much Shock and Killing damage a character can sustain. On a normal human, the damage silhouette is shaped like a human body, with hit locations split into legs, arms, torso, and head. The height of an attack roll determines which hit location takes the damage.

If you’re hit, mark off a wound box for each point of damage sustained. If it’s Shock, put a single diagonal line through each box. If it’s Killing damage, put an “X” through each box.

When new damage strikes a hit location, fill unmarked boxes first, if there are any. Shock damage becomes Killing if all a hit location’s wound boxes are filled. Once all the wound boxes are marked with Shock, any further damage to that location is automatically counted as Killing damage.

Healing

Damage is nasty stuff, so you’re naturally wondering how to get rid of it.

Healing Shock Damage

Shock can be healed with the First Aid Skill, if you have the right tools—a complete first aid kit with bandages, splints, and painkillers usually does the trick. The character performing first aid makes a First Aid roll with the total amount of damage in the hit location as a Difficulty number, up to a maximum of 10 (so if a limb has 2 Killing and 4 Shock damage, the Difficulty is 6). Each successful use of the First Aid Skill heals a number of Shock points equal to the width of the roll; a failed roll, however, inflicts 1 point of Shock.

First aid can be used once per wound. To keep track, simply put a check mark next to the hit location each time you take a wound and erase it when you get first aid.

First aid can never heal Killing damage—only real medical treatment can do that.

Shock can also be healed with rest. Every game day, if you get a good night’s rest, you recover half the Shock damage on each hit location (if you have only 1 point of Shock on a location, it heals completely).

Healing Killing Damage

Killing damage takes a lot longer to heal. Short of some kind of superhealing Miracle, it can only be cured by serious medical attention—meaning surgery and a hospital stay, or prolonged bed rest.

When you get real medical treatment, the doctor must roll Medicine; the First Aid Skill does not apply. The procedure converts a number of Killing points to Shock equal to the height of the successful roll.

With modern equipment it takes 5 – width hours; with more advanced technology it might take less time, and with primitive techniques it might take longer and entail a grave risk of infection. Each hit location is treated with a separate operation.

You can also recover Killing damage with extensive bed rest. For each week of complete rest, 1 point of Killing is converted to Shock on each hit location. If it’s in a hospital, roll the doctor’s Medicine or equivalent dice pool and convert width in Killing to Shock instead.

Primitive Medicine

If your game takes place in an era before the wonders of antibiotics and soap, healing can be a tricky business. Each time you take Killing damage, put a check mark next to the hit location. If the damage was from a puncture wound, circle the check mark as a reminder. If the Killing damage isn’t healed within 24 hours, make an Endurance roll at Difficulty 2 (or 4 if it’s a puncture wound). If you fail, the wound becomes infected and all natural healing ceases. An infected wound takes 1 Shock immediately. Damage from infection does not heal with rest and cannot be relieved with First Aid or reduced with Willpower. After infection sets in, you can attempt the same Endurance roll once per day to fight it off and begin to heal normally. If it fails, you take 1 Shock each day. If all else fails, somebody can amputate the infected limb; a First Aid or Medicine roll keeps you from bleeding to death.

Mental Trauma

Combat isn’t just hard on the body—it can be devastating to the psyche. And, unfortunately, so can many other things. Witnessing an atrocity such as innocents being gunned down; watching a disaster unfold without being able to help; undergoing torture (or committing it); murdering a helpless victim (even an evil one!); taking massive damage; being ambushed; staring instant death in the face—any of these can cause mental trauma. Any time your character suffers some terrible fright, threat, or injury, you must make a Trauma Check.

A Trauma Check is a Stability Skill roll. If it succeeds, you suffer no ill effects. If it fails, you have a choice to make.

You can remove yourself from the action immediately—whether it’s by simply refusing to do whatever triggered the check, or by turning tail and running, collapsing in a heap, or going all glassy-eyed; the exact response is up to you—and lose half your current Willpower.

Or you can tough your way through it, doing whatever you were trying to do, and lose all your current Willpower.

If you have a Base Will score but no Willpower—most humans who don’t have powers are in this camp; so are Talents who run out of Willpower—you lose 1 Base Will if you tough it out, none if you collapse or flee. If you run out of Base Will, things get bad; see Zero Base Will Points, page 52.

Moral Choices

A Trauma Check is required for torturing or murdering a helpless victim because, well, those actions cause terrific psychic trauma to the one who does them. Committing murder is harder on the human mind than nearly anything else. It takes extensive training or indoctrination to inure people to cold-blooded murder, however just their cause.

Unless the GM says otherwise, that means lots of Command or Stability dice—that’s most likely in professional soldiers and snipers—or a Base Will of 0, representing a cowardly butcher who murders out of fear, with no scruples left to violate.

Of course, there are certain people, called sociopaths (or psychopaths), who don’t have this built-in inhibition against murder—even mass murder. Literally inhuman monsters, too, may have no compunctions about it. The GM may decide that such characters can murder without risking men-tal trauma, but such characters should suffer grave penalties to Empathy rolls. An automatic gobble die seems appropriate, making it impossible to make an Empathy check unless the character rolls a width of three or an extra set.

We don’t recommend including player characters in that category. Not that they aren’t free to commit atrocities, but there ought to be a choice involved, a risk, a sense that they may have to give something up if they keep doing it. Murder should matter.

If the GM allows it, when you face a Trauma Check for committing some violent act, you can make the roll before you actually commit the act. That gives you a chance to back away, a moment to choose your course. If you don’t commit the act, you don’t suffer the penalty for a failed Trauma Check. If you commit the act anyway, you suffer the psychic consequences.

Attacking Willpower

Attention, villains! Characters with superhuman powers are vulnerable in one way that they can rarely defend: Their Willpower. If a superhuman runs out of Willpower, all his or her powers suffer. So how do you reduce an enemy’s Willpower? Hit them in the motivations! (See page 54.)

A superhuman who fails to support, uphold or protect the subject of a loyalty or passion loses Willpower. The more important it is to the character, the more Willpower can be lost. Hit them where they live, and it might leave them too weak to fight back when you hit them for real.