The business of roleplaying can be a tough sell to people who have been exposed to the experience previously in an uncontrolled or raw form. Speaking from experience, I have seen people enthused by the prospect turned sour when they saw the size of the average core rule book. The Player Handbook for 4th Edition Dungeons and Dragons is not the sort of thing I would happily hand a player – despite the name – for fear of the repercussions.

I have found the beginner games the best way to introduce a novice player, but they often-times become a beginners set by taking a take on the full rule-set that doesn’t hold true. They might cast aside complexity or ignore whole facets of the game that make the transition to the full game a difficult one. All too easily, you can find yourself trapped in the starter experience because the learning curve to transcend it poses too steep an incline.

The ideal game supports a strong and exciting playing experience with enough rules to handle genuine challenges, but without so much crunch as to frighten away new players. The veterans, in the meantime, need to see some reassuring consistency in mechanics and the reassuring clatter of dice on the table. Many recent games, whether modern and new systems or Old School Renaissance (OSR) creations, have sought to instil this balance of factors into a satisfying base product and game line.

Into The Odd joins the scuffle for simplicity with potential for substance.

Form

Into The Odd comes in both PDF form and as a physical book (due for release in January 2015). The 52-page volume, written by Chris McDowall, comes in a clear, two-column layout scattered with commissioned illustrations from various artists.

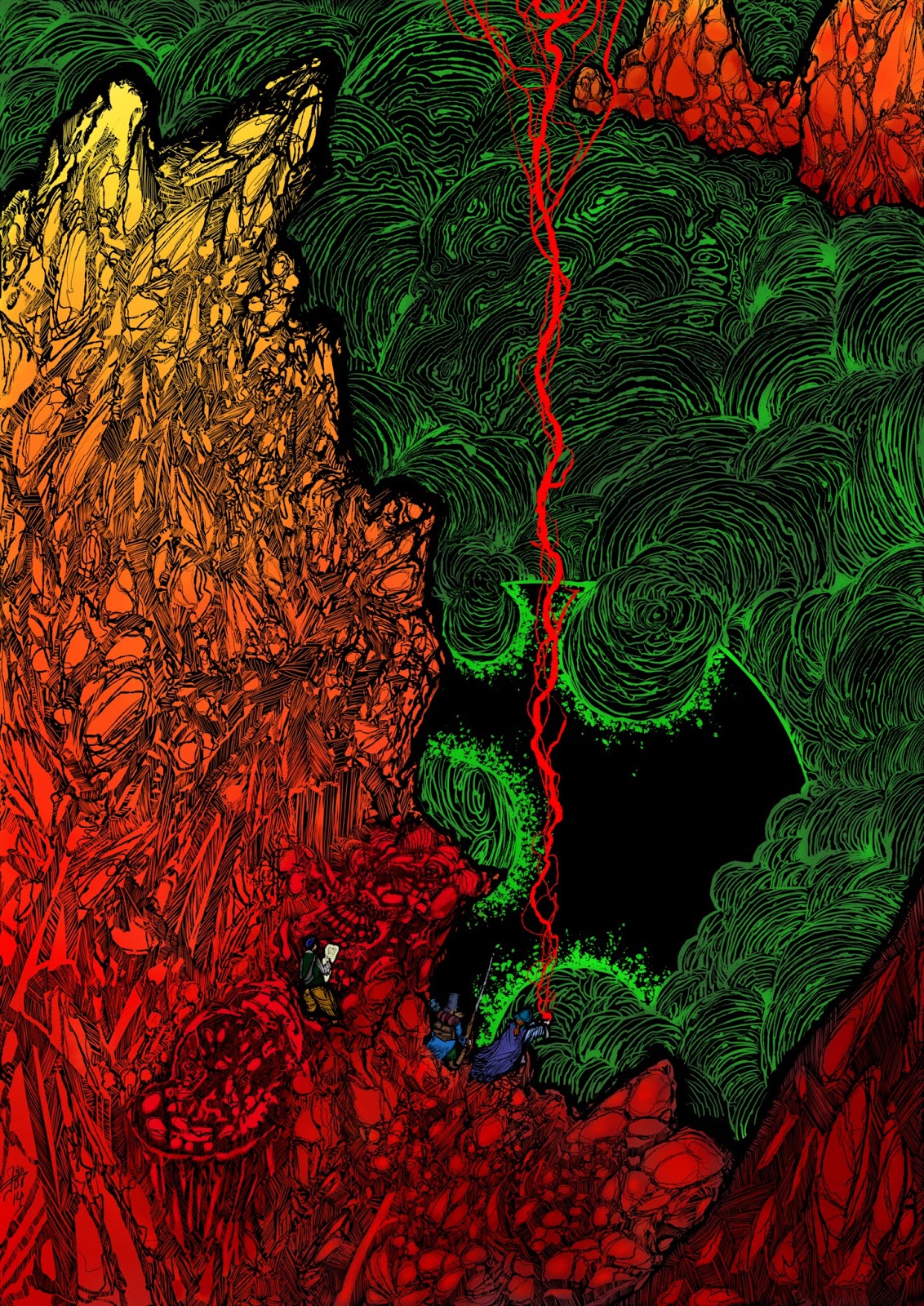

The red and black cover shows a stylised version of the game’s name as the underworld beneath a town. Functional rather than necessarily excellent, the picture is upstaged by the next interior illustration. Jeremy Duncan‘s digital art looks like a small group of adventurers clambering through great spires of orange-red rock with a curling green mist between, the mage in the group calling red lightening down from the heavens. It’s a stunning piece with a depth that’s difficult to appreciate in anything but digital form. I sort of wish it made it to the cover.

The remaining art varies considerable in size and quality (though, each to their own in determining that), but sufficiently get across the sense of the weird that lurks at the heart of this game.

Features

One of the interesting things about Into The Odd comes from the association with OSR. The OSR movement takes the Dungeons and Dragons of yesteryear and recasts it in some way or form, embracing the principles, mechanics, classes, and so forth in greater or lesser measure. Into The Odd has such simplistic system, it sits far out on the OSR spectrum. So little of the original remains, yet in the outcome and presentation you can still hear the Old School call.

The book practically breaks down into three sections – playing the game, running the game, and setting. The actual breakdown comes in chapters, but roughly speaking they fall into the three areas.

The first – playing – explains about character creation, advancement, organisations and arcanum.

Your Character is simple to create and means that if you suffer an unwanted or unexpected fatality, a new character is a work of moments to generate. You have three Abilities – Strength, Dexterity and Willpower – rolled with three 6-sided dice each, and Hit Points rolled with a single die. Once you have rolled these up, cross reference your highest Ability Score with your Hit Points to get your Starter Package, a few pieces of equipment to get you going.

The Starter Package means you always start with a weapon of some form, along with a several other more esoteric or arcane items like glue, manacles or an accordion. The odder equipment makes for an interesting way to give personality to classes and featureless characters. The game doesn’t include an specific class system – like warrior or thief – racial subtypes, or even any set of occupations. You have full control of who and what you are. The Starter Package can be a guide, but you have the final say.

The basic dice rolling and random equipment means that you have a character ready in less than a minute. From that point you can get straight into playing the game.

Once you do play the game, the business of Character Advancement comes down to participation and survival rather than careful accounting and administration. You advance by coming back from expeditions alive and, eventually, by taking on an apprentice and seeing them through an expedition with you. You also have the option to take on hirelings to get through those tough adventures, who might yet ascend to full character status if you want an excuse for replacing a dead companion at a moments notice.

For those with greater aspirations, Companies and War explains the business of taking the challenge up a level. Companies start from small groups and expand in their influence and potential. Taking on apprentices and trained soldiers, membership brings growth and wealth, and ultimately power.

A lot of this harkens back to the Dungeons and Dragons of old, as the later boxed sets saw characters rise above petty murder and thievery in dungeons to assassination and pillaging in courts and across national boundaries. Into The Odd does it in a few scant pages – but gets across the flavour and offers up the raw mechanics.

Playing the Game boils the mechanics down to a single page. If a player characters wants to do something, they can – if it seems reasonable and they can take their time. You can batter down a locked door if you want – it doesn’t take any special skills. However, if you want to do it quickly, quietly or without a trace of evidence, that means a Save. The Referee chooses an Ability and you need to roll equal to or under it on a 20-sided die. Batter down the door with brute force using a Strength Save, or defeat the locking mechanism without evidence using a Willpower Save.

The system uses a very straight forward and brutal system of conflict, where you always hit. Your character’s weapon determines damage rolled, subtracting the opponent’s armour, and that then comes off Hit Points. Once you run out of Hit Points, damage starts chipping away at Strength and then you’re in trouble. Once damage cuts into Strength, you need to make a Strength Save to avoid Critical Damage at which point further action becomes impossible without attention and rest.

The rules appeal to me as straight forward and open to interpretation to suit most circumstances. You resolve challenges with Saves and failure means problems, a world of hurt, and maybe death. However, death isn’t a problem because another character can come back into the situation with very little effort at all. You’re a troupe of adventurers supported by nameless servitors, underlings and hangers-on, until one of them feels the urge to step up. Ideal beer’n’pretzals gaming where the fun and story comes ahead of the crunch.

The next three pages and a page size illustration handle Arcana. Some characters will acquire a piece of arcanum as part of their Starter Package, while other will come from adventuring. These pieces of magical, alien or quasi-technological paraphernalia replace the need for spells or blessings – though the game is sufficiently wide open that fans have already suggested – and written up – rules for more structured magic.

This made me think of Numenera. Then, I remembered that the reason Numenera came to mind was the knowing nod that system gives the original Dungeons and Dragons game where treasure, magical and otherwise, flowed like water. In the old days, treasures formed part of the equation for character experience accumulation. It makes sense to reward the characters here with a generous scattering of such items because (a) they have a very short life expectancy and (b) the more stuff they have the bigger a target they become for the greedy and envious.

Characters who get an item from their Starter Package roll randomly from the Powers You Cannot Understand table. The referee can populate her adventures with more items based on those here, or with examples taken from Powers You Can Barely Control and Powers You Shouldn’t Control tables. Black Hole Collider, anyone?

An Example of Play bridges the gap into the Referee section and provides an good example of play, the mechanics and a touch of the oddness. This serves as useful reference for players and referee alike in grasping what play should involve.

What Do You Need to Know to Be the Referee? handles the business of getting a grip on the mechanics and running an entertaining game. It offers basic and straightforward advice, useful to anyone. Aside from discussing the mechanics already outlined, it also offers up Luck Rolls as a Referee mechanism to add randomness to the game. Roll a single 6-sided die, interpreting a high as good for the players and a low as not so good.

How Do You Bring the World to Life? explains how every character and monster should have a purpose, and in that desire provides a focus for the way the Referee plays them. Monsters have armour, hit points, and other characteristics, like the players, along with Special Abilities that sometimes break the rules. The OSR core to the game means that you can take a creature from a similar game and quickly port it over to Into The Odd. Chris has posted several quick conversions on his blog and social media channels – and it works with similar speed to character generation.

While the game includes a page of sample monsters, the section suggests making all adversaries unique to maintain the interest, wonder and oddness of the game. This seems like a fair aspiration for any game runner.

Pages on Treasure and Traps dealing with the creation and presentation of these key aspects of an adventure. Both use the same simple and straightforward approach, making for easy adaptation of ideas, both original and pinched from other games.

The third section – The Odd World – provides an outline of the setting in brief. Very brief. Sufficient information exists for you to hang your game off, but doesn’t constrain you. The key city of Bastion serves as the hub for civilisation, a place exhibiting aspects of medieval and industrial existence. Factories provide mass produced goods, while the poor and down-trodden scrape an existence between the wealthy and corrupt above, and the twisted and murderous below. Beyond Bastion, the land grows untamed as populations have abandoned a rural life for the promise of the city. Far realms promise wealth to those who seek it, served up in equal measures with death, magic and insanity.

The best bit of the setting is the adventure, The Iron Coral. This first expedition has something of the stripped down playset-style of Dungeon World about it, with a numbered map explained through keywords and dangers. The really neat bit is that beyond The Iron Coral is The Fallen Marsh, a hex mapped area of encounters outside the dungeon. And, if you make it through the marsh you will find Hopesend, the Last Port of the North.

Totalling 10-pages, this setting feels like the classic game again, offering dungeons to the newcomer, the outdoors to the experts, and the politics and skulduggery of the cities beyond. I think it would be a perfect way to run this example as well, side-stepping getting the job to go straight to the first encounter and introduce Into The Odd with blood, battle, traps and arcana.

The book rounds off with a slew of random tables for creating encounters, situations, city personalities, council decisions and more. As a quick stop for a fresh idea, they provide a solid starting place – and again, Chris has not been shy in writing many more of these to fuel creativity. A set of Rory’s Story Cubes and a copy of Jason Sholtis’s The Dungeon Dozen wouldn’t go amiss either – and should give you enough adventure ammunition to last a lifetime.

Final Thoughts

Into The Odd provides an highly condensed and stripped down tabletop gaming experience in the Old School style, without the ponderous bloat of many modern games. While some of the art is a bit weak and complete newcomers might struggle if they believe that rules must make the game, Chris McDowall has delivered an impressive little rule-set that has undergone lengthy playtesting, feedback and mechanical change.

As a starter game, a pick-up for veterans, or a quick convention drop, Into The Odd definitely delivers and will certainly sit on my mobile device for quick access – and in my convention kit, once the physical copy comes out in January. The author’s energy and willingness to support and expand the game further suggests – one hopes – we will see more Odd to come.

Into The Odd is available from the Lost Pages web store, as either PDF only or Print and PDF offer, from $7.99.